Superman and World War II

On February 27, 1940, Look magazine featured a two page comic strip by

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster

titled "How Superman Would End the War." Superman simply abducts Adolf Hitler

and Josef Stalin, then brings both leaders before the League of Nations in

Geneva, Switzerland.

The cartoon drew criticism from the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda. On April, 25,

1940, Das Schwarze Korps, the weekly newspaper of the Schutzstaffel

(SS), reprinted the strip with an antisemitic response titled "Jerry Siegel

greift ein!" The hit-piece places the Kent farm in Des Moines, Iowa. The

author concluded that "Jerry Siegallack stinks," a pun on the German word for

sealing wax.

On December 6, 1940, the government of Canada enacted the War Exchange

Conservation Act (WECA), restricting the importation of all non-essential

luxury goods. Comic book and pulp imports from the United States were

banned from Canada until 1946.

On May 20, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8757

Establishing the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD). Regional youth programs

were created throughout the country including the

Superman Junior Defense League of America,

Roberts Superman Defense League, and the Superman Victory Kid Club. In the comic books,

Supermen of America Club

advertisements began encouraging readers to buy Savings Bonds and Defense

Stamps in Action Comics #43, on sale October 14, 1941.

The United States Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, was attacked by the

Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service on December 7, 1941. Congress declared war

against Japan on December 8, followed by Germany on December 11. The Writers'

War Committee, later renamed the Writers' War Board (WWB), was created on

January 6, 1942. The civilian board was funded by the Office of War

Information. The WWB worked to control the war narrative in all forms of

American media, advising publishers on how to portray the Axis. Comic books

became a powerful weapon of propaganda for civilians and soldiers.

Like Uncle Sam and Rosie the Riveter, Superman was an important symbol of

American patriotism during the second World War. The Action Comics and

Superman books were spared from government paper rationing. Although

the comic book stories mostly avoided the war, Superman battled the enemy on

covers,

on the radio, in

cartoons, and in the newspapers.

A German machine gunner is seen on Action Comics #35 (April 1941),

and German troops on Action Comics #39 (August 1941). A Wehrmacht

tank appears on Action Comics #40 (September 1941), and a Nazi

paratrooper is featured on Action Comics #41 (December 1941).

Patriotic covers illustrated by Fred Ray began appearing with

Superman #12 (September–October 1941).

Supermen of America

ads prepared with the Department of War showcased twelve individual

"Supermen of the U.S. Army" in Action Comics #49–60 (June 1942–May 1943).

In the newspaper storyline from February 16–19, 1942, Clark Kent attempts to

enlist in the Army, but fails the eye exam with his X-ray vision. A

disgusted

Lois Lane

remarks, "I might have known the Army would turn you down." Clark decides

that the U.S. Armed Forces are capable of achieving victory without

Superman. In the August 20, 1943, strip, General Douglas MacArthur informs

Superman that the United Nations does not need him. In the comic books, Clark

worked with the Army Air Force Technical Training Command in

Superman #25 (November–December 1943), and the U.S. Navy in

Superman #34 (May–June 1945).

Superman supported the war effort from the home front by educating soldiers

and raising money for the Allies. In April 1942, the Navy Department

classified comic books as essential supplies for sailors and Marines.

Superman titles were shipped to troops at Midway Garrison. That month, a

"Sooper Man" comic book appeared on the cover of

Army Motors. Harry Donenfeld and Superman Inc. later produced an

official comic strip for the magazine that informs soldiers about preventive

equipment care. The influx of comic books and other reading materials led to

increased literacy rates within the ranks.

Tim's Pie Eaters Club was originally established by

Streeter Blair

in January 1925. The campaign was reorganized as the

Superman-Tim Club

in July 1942. Monthly issues of Superman-Tim were distributed to

clothing retailers nationwide. Superman and Tim encouraged children to

purchase War Bonds and salvage scrap material for the defense effort.

Wartime storylines featured an international Nazi spy known as Brown

Scorpion, as well as Japanese saboteurs.

Comic book readers were constantly reminded to purchase War Bonds and War

Stamps. Later marketing focused on the War Loans.

World's Finest Comics #8 (Winter 1942) portrays Superman, Robin, and

Batman encouraging children to "Sink the Japanazis with Bonds & Stamps."

The cover of Action Comics #58 (March 1943) depicts Superman printing

propaganda posters that read, "Superman says: You can slap a Jap with War

Bonds and Stamps!"

"Japanazi" was a popular slur promoted by the War Production Board and War

Stamp Council. Since the late 19th century, Asian people were commonly

represented as caricatures in American media. Asian villains were often

depicted with buck teeth, glasses, and a Fu Manchu mustache. All three

features are included in the "Jap Spy" character from the Superman animated

short Japoteurs, released on September 18, 1942, by Paramount

Pictures and Famous Studios. Superman thwarts a gang of Japanese saboteurs

attempting to hijack a bomber plane.

The "never-ending battle for truth and justice" motto was updated to "truth,

justice, and the American way" on

The Adventures of Superman

radio series. The variation first appeared during episodes of "The Wolfe,"

an 11-part Nazi storyline that aired on Mutual from September 2–15, 1942. In

a letter to the Office of War Information dated April 12, 1943, show creator

Robert Maxwell declared his intent to teach hatred towards the enemy.

Maxwell wrote, "A German is a Nazi and a Jap is the little yellow man who

'knifed us in the back at Pearl Harbor.'" By 1944, the WWB advised media

outlets to portray all German citizens as enemies rather than ordinary

people.

From February 19, 1942, to March 20, 1946, over 125,000 people of Japanese

descent were imprisoned in concentration camps throughout the United States.

The majority of detainees were American citizens. In the June 28, 1943,

Superman newspaper strip, Clark and

Lois begin

investigating "a typical Jap relocation camp" named Camp Carok. Lois praises

the facility saying, "The Jap government should have absolutely no excuse

for not showing their prisoners of war as much consideration." On June 30,

the plot was retold in the Tulean Dispatch Daily, a mimeographed

newspaper published by detainees of the Tule Lake Segregation Center in

Newell, California.

On July 9, 1943, Superman used "his amazing muscular control" to disguise

himself as a Japanese prisoner named Masu Watasuki. Superman comments,

"It's easy – to make myself – look like a Jap. Take a-lookie at the new

Watasuki!"

Superman remained disguised as Watasuki until July 17.

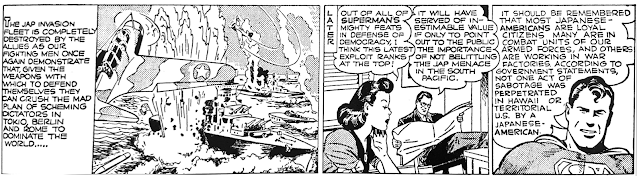

The Camp Carok plot drew criticism from readers nationwide. After destroying

a Japanese fleet on August 21, 1943, Superman delivered a backtracked

response: "It should be remembered that most Japanese-Americans are loyal

citizens. Many are in combat units of our armed forces, and others are

working in war factories. According to government statements, not one act of

sabotage was perpetrated in Hawaii or territorial U.S. by a

Japanese-American."

An "Overseas Service Edition" of Superman #27 and "Overseas Edition"

of Superman #28 were distributed to the Armed Forces in 1944 by the

U.S. Army Special Services Division. From November 1944 to April 1945, the

U.S. Navy released six "Special Edition" comics that reprint issues of

Action Comics and Superman. The "Special Edition" books

include educational material produced by the Bureau of Naval Personnel.

A Boeing B-17 named Superman (41-24380) was the oldest Flying

Fortress of the 97th Bombardment Group in North Africa. The nose paintings

are based on a promotional image for the 1941 animated

Superman series from Fleischer Studios and Paramount Pictures.

Superman was assigned to the 340th Bombardment Squadron, 97th

Bombardment Group at RAF Polebrook, England. The aircraft was photographed

by Margaret Bourke-White for Life magazine in September 1942. On

October 11, 1942, the bomber was assigned to Maison Blanche airfield in

Algeria. Superman received over 300 holes with no fatalities while

piloted by 1st Lt. John A. Gallup. Six of the crew members were awarded the

Purple Heart.

Superman was later assigned to the 515th Air Service Group. On

September 15, 1945, the bomber sent a distress call while enroute from

Dakar, Senegal, to Natal, Brazil. Major Willard E. Karschnick ditched the

aircraft in the Atlantic near the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago.

All 14 crew members were promptly rescued by Brazilian destroyer Greenhalgh

(M 3) about 500 miles off the northeast coast.

A Consolidated B-24D Liberator (41-23938) named Super Man was

assigned to the 11th Bombardment Group, 98th Bombardment Squadron in the

Pacific. Images of Superman holding a hammer and a bomb were painted on the

nose of the plane. On April 20, 1943, Super Man was heavily damaged

by anti-aircraft fire and Japanese Zero fighters over Nauru. Radio

Operator/Waist Gunner Corporal Harold V. Brooks was mortally wounded. On May

5, The New York Times reported that ground crewmen counted 500 holes,

later confirmed as 594. The mission is depicted in the 2014 film

Unbroken, written by the Coen Brothers and directed by Angelina

Jolie. The film is based on the biography of bombardier Louis Zamperini by

Laura Hillenbrand,

Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption.

After repairs, a new aircrew renamed the bomber

Sexy Sue-IV, Mother of Ten and a nude woman was painted on the nose.

During a bombing run from Tarawa on January 20, 1944,

Sexy Sue-IV reported engine failure near Wotje Atoll, Marshall

Islands. The fate of the nine crew members is unknown. Classified material

from the aircraft was later captured from Japanese forces on Kwajalein

Atoll.

-

Like Clark Kent,

Joe Shuster

received a 4-F disqualification and was declared "unfit for military

service" due to his failing eyesight. The Shuster Shop continued to produce

Superman features and Joe would contribute illustrations for bond drives.

Jerry Siegel

was drafted in the U.S. Army and enlisted on June 28, 1943. Siegel was sworn

in during an induction ceremony at the "Festival of Freedom" on July 4. Over

80,000 people attended the celebration in the Cleveland Municipal Stadium.

Jerry later revealed, "While I was in the Army, practically all of the

Superman stories were ghosted."

In August 1943, Private Siegel reported to the 39th Special Service Company

for Basic Training at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland. Jerry and Joe provided

an exclusive Superman strip for The Fort Meade Post on August 13, 1943. In a

guest article, Jerry wrote that the "real Supermen" were the members of the

Armed Services. The September 10, 1943, issue of

Yank, the Army Weekly quotes Jerry on Superman: "he'll never join the

army; he'll never help me."

After Basic Training, PFC Siegel was stationed in Elkins, West Virginia, as

part of the Detached Enlisted Men's List (DEML). In November 1943, Jerry was

assigned a 1,500-word weekly column providing updates on Special Service

activities for The Inter-Mountain newspaper. Jerry spent the fall and

winter living in a five-man tent in the rugged hills of the West Virginia

Maneuver Area (WVMA). In a letter dated January 1, 1944, Jerry asked DC

Comics co-founder Jack Liebowitz to send 131

Supermen of America

membership kits for the company. The soldiers wanted to wear the membership

buttons as insignia.

Jerry received additional training at Camp Siebert, Alabama, before

reporting to Hickam Field in Honolulu, Hawaii. The front page header of

Midpacifican on August 26, 1944, proclaimed "Superman's Old Man

Here." Jerry is unflatteringly pictured with his gear and labeled a "Sad

Sack."

The following day in Waikiki, Jerry met his childhood idol Edgar Rice

Burroughs, the creator of Tarzan and John Carter of Mars. Both characters

were major influences on the

creation of Superman. Jerry sketched a profile portrait of Superman for Burroughs, praising the

author as "the daddy of today's leading heroes."

Jerry Siegel was promoted to Technician Fifth Grade (T/5), equivalent to

Corporal. Siegel wrote stories for Hickam Highlights, a raunchy

mimeographed base newsletter, and joined Midpacifican as a staff

reporter in September 1944.

Jerry collaborated with artist Ben Bryan on a "Super Sam" comic strip. The original artwork depicts an unauthorized Superman appearance.

Jerry collaborated with artist Gerald H. Green on "Super GI," a weekly

cartoon published in Midpacifican from December 30, 1944, to March

17, 1945. A photograph of Siegel and Green reviewing the artboards was later

printed in Army Life. Super GI, also known as Joe Droop, is in love

with Corporal Jane Troy. Woman's Army Corps Pvt. Faye Lewis Trowbridge from

Dallas, Texas, was a model for Jane Troy.

On April 14, 1945, the Superman newspaper strip featured a cyclotron,

or "atom smasher." At the time, the Manhattan Project was highly classified

and the Trinity nuclear device had not been tested. The Office of Censorship

instructed editor Jack Schiff to end the storyline. The FBI contacted Jerry

for questioning, but "The Science of Superman" story was ghost written by

Alvin Schwartz. Schwartz had read an article about the cyclotron in the

April 1936 issue of Popular Mechanics.

The Adventures of Superman

radio show had previously featured "Dr. Dahlgren's Atomic Beam Machine" in

February 1940, before the Manhattan Project was established.

On May 14, 1945, Midpacifican was replaced by the Middle Pacific

edition of The Stars and Stripes. As a staff reporter, Jerry wrote an

article titled "Melt to Music" printed on May 30. From June 5, 1945, to

January 15, 1946, Jerry contributed a daily humor column called "Take a

Break with T/4 Jerry Siegel." The column was renamed after his promotion to

Technician Fourth Grade on July 11.

On August 11, 1945, Jerry appeared on "Breakfast at the Crossroads," a

weekly radio show on KGU broadcast from the USO Rainbow Club in Honolulu.

Jerry judged contest answers for the question, "What would you do if you

could be Superman for five minutes?" The winning answer was, "I'd take a

fast trip home." The contest was sponsored by the USO and the American Red

Cross.

The war officially ended on September 2, 1945. On January 21, 1946, Jerry

was discharged from the Army and sent home to Cleveland.

-

Agostino, Lauren, and A. L. Newberg.

Holding Kryptonite: Truth, Justice and America's First Superhero.

Holmes & Watson Publishing Co., 2014.

Anderson, M. Margaret.

"Racism: Cause and Cure."

Pittsburgh Courier, 10 July 1943, p. 5.

"Creator of 'Superman' to Appear on Airshow." The Stars and Stripes, Middle Pacific edition, 10 August 1945.

Cummings, Roy. "Creator of Superman is on Duty in Honolulu as an Army Corporal." Honolulu Star Bulletin, 23 August 1944, pp. 1, 6.

Duke, John. "Fathers of Tarzan, Superman, Renfrew Meet." Midpacifican, vol. 3, no. 19, 2 September 1944, pp. 1, 11.

"Faster Than a Bullet."

Daily Tulean Dispatch, 1 July 1943, p. 2.

Freeman, Roger, and David Osborne. The B-17 Flying Fortress Story. Arms and Armour Press, 2000.

Freeman, Roger, and David Osborne. The B-17 Flying Fortress Story. Arms and Armour Press, 2000.

Hayde, Michael J.

Flights of Fantasy: The Unauthorized but True Story of Radio & TV's

Adventures of Superman. BearManor Media, 2009.

"Here's What G-1 Supers Would Like." The Honolulu Advertiser, 12 August 1945, p. 12.

Hillenbrand, Laura. Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption. New York, Random House, 2010.

"Introducing 'SUPER GI'." Midpacifican, 30 December 1944, p. 10.

"Jerry Siegel greift ein!" Das Schwarze Korps, 25 April 1940, p. 8.

Levitz, Paul. 75 Years of DC Comics: The Art of Modern Mythmaking. Taschen, 2010, p. 178.

McCarthy, Tom. "The Story of Sexy Sue, Mother of Ten." 11th Bombardment Group Heavy (H) "The Grey Geese", 11 February 2012.

"Miler Zamperini as Bombardier, Had 'Toughest Race' on Nauru Raid." The New York Times, 5 May 1943, p. 6.

"Here's What G-1 Supers Would Like." The Honolulu Advertiser, 12 August 1945, p. 12.

Hillenbrand, Laura. Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption. New York, Random House, 2010.

"Introducing 'SUPER GI'." Midpacifican, 30 December 1944, p. 10.

"Jerry Siegel greift ein!" Das Schwarze Korps, 25 April 1940, p. 8.

Levitz, Paul. 75 Years of DC Comics: The Art of Modern Mythmaking. Taschen, 2010, p. 178.

McCarthy, Tom. "The Story of Sexy Sue, Mother of Ten." 11th Bombardment Group Heavy (H) "The Grey Geese", 11 February 2012.

"Miler Zamperini as Bombardier, Had 'Toughest Race' on Nauru Raid." The New York Times, 5 May 1943, p. 6.

Myer, Dillon S.

"Superman May Help Evacuees."

Gila News-Courier, vol. 2, no. 91, 31 July 1943, pp. 1–2.

Rankin, William H., Jr. "Value of the Handicraft Branch of the Special Services Division of the Army Service Forces forcefully demonstrated now." Army Life and United States Recruiting News. October 1945, p. 19.

Siegel, Jerry. Creation of a Superhero. Draft. 1979.

Siegel, Jerry. Letter to Jack Liebowitz. 1 January 1944.

Siegel, Jerry. "Not all Men of Tomorrow are in Comics, Siegel Says." The Fort Meade Post, 13 August 1943, p. 9.

Rankin, William H., Jr. "Value of the Handicraft Branch of the Special Services Division of the Army Service Forces forcefully demonstrated now." Army Life and United States Recruiting News. October 1945, p. 19.

Siegel, Jerry. Creation of a Superhero. Draft. 1979.

Siegel, Jerry. Letter to Jack Liebowitz. 1 January 1944.

Siegel, Jerry. "Not all Men of Tomorrow are in Comics, Siegel Says." The Fort Meade Post, 13 August 1943, p. 9.

Siegel, Jerry (w), and Shuster, Joe (i).

"How Superman Would End The War."

Look, 27 February 1940, pp. 16–17.

"Six-Million Volt Atom Smasher Creates New Elements." Popular Mechanics, vol. 65, no. 4, April 1936. p. 580.

"Sooper Man." Army Motors, vol. 3, no. 1, April 1942.

"Superman's Dilemma." Time, vol. 39, no. 15, 13 April 1942, p. 78.

"Six-Million Volt Atom Smasher Creates New Elements." Popular Mechanics, vol. 65, no. 4, April 1936. p. 580.

"Sooper Man." Army Motors, vol. 3, no. 1, April 1942.

"Superman's Dilemma." Time, vol. 39, no. 15, 13 April 1942, p. 78.

"'Superman' Finds Action at Relocation Center."

Tulean Dispatch Daily, vol. 5, no. 87, 30 June 1943, p. 2.

"Superman in Relocation Center."

Gila News-Courier, vol. 2, no. 78, 1 July 1943, p. 2.

"Superman -- Nazis Say He's a Bad Influence."

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 7 May 1940, p. 5.

"Superman Quiz."

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 11 August 1945, p. 16.

"Um destróier brasileiro salva 14 tripulantes de uma Fortaleza Voadora sinistrada em atlo mar." Jornal do Brasil, no. 220, 19 September 1945, p. 5.

"Um destróier brasileiro salva 14 tripulantes de uma Fortaleza Voadora sinistrada em atlo mar." Jornal do Brasil, no. 220, 19 September 1945, p. 5.

"Unfavorable Comment Voiced on Superman."

Des Moines Register, 20 July 1943.

Watcher, Wally. "GI Hollywood Star Here." Midpacifican, 26 August 1944, p. 1.

Watcher, Wally. "GI Hollywood Star Here." Midpacifican, 26 August 1944, p. 1.

Weisinger, Mort. "Here Comes Superman!" Coronet, July 1946, pp.

23–26.

%20by%20Joe%20Shuster.png)

%20by%20Fred%20Ray.png)

%20by%20Fred%20Ray.png)

%20by%20Fred%20Ray.png)

%20by%20Fred%20Ray.png)

%20by%20Fred%20Ray.png)

%20by%20Jack%20Burnley.png)

%20by%20Jack%20Burnley.png)

%20by%20Wayne%20Boring%20&%20Stan%20Kaye.png)

%20by%20Jack%20Burnley%20and%20Stan%20Kaye.png)

%20Philips%20-%20B-24D-13-CO%2041-23938%20Super%20Man,%20c.%201943.png)

%20by%20Wayne%20Boring.png)

%20by%20Jack%20Burnley.png)